Westmont Magazine Being There: Westmont and International Education

Photo by Keaton Hudson ’14

by Mark Sargent, Provost at Westmont

Over soup a few years ago, some colleagues and I recounted the moments when we realized that the world is flat. I recalled a visit to the sweeping grassland of the Maasai Mara where a young Kenyan boy—barefooted, tending goats—handed out cards with his family’s email address. A friend described meetings in Seoul and Bangalore—both on the same day, via Skype. As we told our tales, one colleague conceded that the world may have “more and more level places” but reminded us “that there are still mountains beyond mountains.”

I think of that comment when I consider the future of international education. The spark for our lunchtime conversation was Thomas Friedman’s “The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century.” In that buoyant survey of the global economy, Friedman traces how technology is leveling many political and economic barriers to international competition and cooperation. Four years after the attack on the World Trade Towers, he worried that Americans had been ignoring many other vital global trends, such as the rising wealth and creativity of the middle class in the world’s two largest nations,China and India. In a recent column in the New York Times, Friedman extends his optimism about new technologies to the emerging MOOCs—the massive, open, online courses that heavy weights like Harvard, MIT and Stanford offer. Such courses, he claims, can help alleviate poverty in the developing world by increasing access to low-cost education.

About the time op-ed pieces debated Friedman’s theses, another journalist, Tracy Kidder, released his own narrative about those still cut off from the benefits of the global network. “Mountains Beyond Mountains” recounts the extraordinary persistence of the physician Paul Farmer, co-founder of Partners in Health, who spent years venturing over the rugged back-country of Haitito bring basic health care to the diseased and the poor. The title of the book takes its cue from an old Haitian proverb, a reminder that peaks and valleys still isolate communities. We may live in a global village, but our daily lives are local. While new technologies and transnational partnerships have done much to raise the quality of life in many regions of the developing world, some of the world’s disparities have grown more acute in the era of globalization. Technology gives us considerably more lenses on the world, but there are still things we can only know by being there.

Westmont has built a strong heritage of international study. At present, more than 60 percent of our students complete a program off campus before they graduate, a rate that exceeds the Ivy League and is ten times greater than the national average. We hope to sustain and expand this heritage. Yet international education worldwide has been changing in both inspiring and disquieting ways. How can we embrace the emerging opportunities of our shrinking world and still maintain the moral vision of the Christian conscience? Let me offer a few thoughts, largely personal, about the flatlands and the mountains that loom before us.

In 1986, shortly after my wife, Arlyne, and I were married, we moved to the Netherlands, where I spent two terms teaching American literature at the University of Utrecht. Supported by the Fulbright program, we received an amiable welcome from our Dutch colleagues, settling into an apartment in the medieval heart of town. Each morning we woke to the thunder of the old cathedral bells and walked through shadows of the Cold War. As I ventured to class alongside the canal, I passed a satiric poster of the Statue of Liberty dressed in a tiara of MX missiles. One of my tasks was teaching a course on “American Mythologies” and explaining the sources and scope of “America’s moral burden” to remedy the world. Among students and faculty, there was an allure, even admiration at times, with American ingenuity, though considerable fretfulness about the nation’s foreign policy. Conversations about Mark Twain and William Faulkner wandered occasionally into the abrupt end of the Reagan-Gorbachev summit in Reykjavik or the latest disclosure in the Iran-Contra affair. Harry Mulisch’s novel “The Assault”—about the lingering specter of World War II on Dutch memory and politics—was the source for that year’s Oscar-winner as Best Foreign Language Film. No one predicted the imminent fall of the Berlin Wall.

At that time, my grant to the Netherlands could still be considered part of the Fulbright program’s investment in cross-cultural under-standing, or what is favorably described as “soft diplomacy.” In the wake of World War II, Senator William Fulbright urged the United States to devote some of its war dividend to international scholarly exchanges, designed in large measure to promote empathetic imaginations and to reduce inclinations toward violence. The Fulbright program still sponsors such endeavors. Westmont’s political science professor Susan Penksa received two Fulbrights to contribute to the political discourse about peace and security in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

But today a large portion of the international exchanges—Fulbright and otherwise—are envisioned as research or professional collaborations rather than as diplomatic ventures. There is much to celebrate here: the decline of Cold War anxieties in Europe, greater knowledge and communication through technology, and the advances of international universities. Forty years ago, the United States dominated the publication of scholarly articles in the sciences, but the European Union moved ahead in the mid-1990s. Since 1995, the number of science articles American scholars publish each year has grown only modestly, whereas China’s output has increased by 17 percent. Today the elite research institutions in the United States are as likely to promote joint neuroscience research with Fudan University in Shanghai or University College London as to sponsor exchanges for cross-cultural understanding.

Any future for global study, I believe, should lead toward more opportunities for our students to participate in international research. Technology is making that possible for undergraduates in increasing ways. In a recent address at the University of Virginia, Provost John Simon, a chemist, describes his electronic friendship with his primary Japanese collaborator. Simon contends that comprehending the global nature of research will become one of the most essential fruits of a liberal arts degree. So often we speak of the liberal arts as the best way of preparing for a life of learning; in the coming decades the pursuit of knowledge will likely require many of our graduates to work with colleagues across borders. NAFSA: Association of International Educators has been announcing new incentives for undergraduate research around the world. A recent initiative focuses on environmental sustainability, a topic of intense interest to students from many nations, who know that contaminated rivers run across boundaries and carbon emissions don’t honor national airspace. This new push in under-graduate research seeks to find ways of engaging more science majors in international study. Collegians pursuing the health sciences make up 14 percent of the domestic college population, but only five percent of those who study overseas.

A global lens can also help us blend the cultures of inquiry and service, part of the vision for integrating faith and learning that has long defined Christian education. Despite that goal, programs of ministry and education have often tensely co-existed at Christian colleges and sometimes competed for students’ loyalty. Some of Westmont’s traditions of ministry—notably, Potter’s Clay and the Emmaus Road programs—can embrace compelling new opportunities for blending scholarship and service.

About a decade ago, I first visited a research farm in Florida devoted to developing new drought-resistant seeds; students there participated in research endeavors that relied on the help of missionaries and Christian social workers overseas. Some notable advances in health care, hunger relief, microbusiness, agriculture, and conflict resolution occurred because of the trust and understanding that developed during decades of Christian workers and churches living and working within local communities. At their best, short-term ministry projects overseas nurture great respect for the work of indigenous churches and NGOs and inspire liberal arts students to understand how matters of the heart often require the long discipline of the mind.

Despite some excitement about new research programs, the International Association of Universities (IAU) has recently expressed fears that “prestige” or “economic advantage” has displaced “soft diplomacy” as the core purpose of collegiate international programs. According to IAU, many universities are forming international collaborations primarily to bolster revenues from research and to secure higher rankings. The idea that international study can nurture empathy, “mutual respect,” “fair partnership,” and the moral imagination can easily be lost.

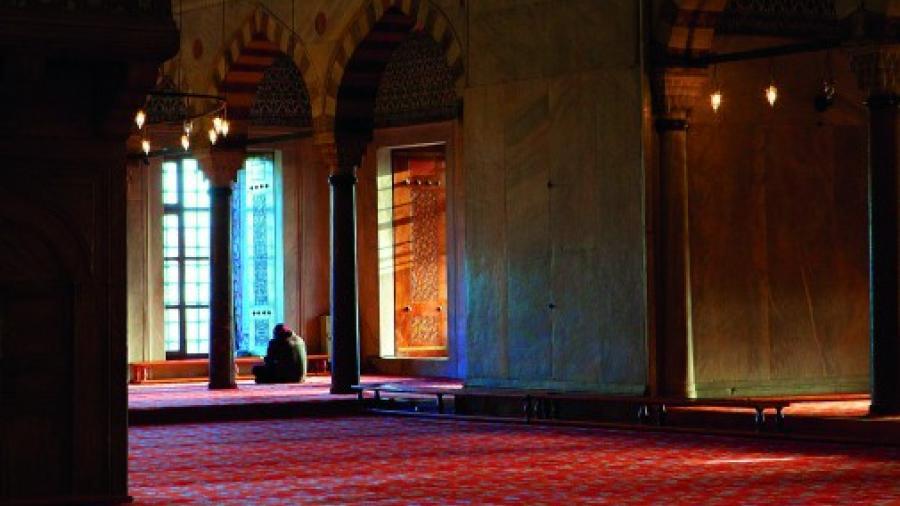

Westmont can both claim and enrich that heritage. Last summer, Deborah Dunn and Caryn Reeder led a trip to Northern Ireland and the Middle East that focused on exploring conflict and reconciliation in nations that have been caught in a crucible of religious distrust and retaliation. In an October forum on campus, Deborah recalled the moment when she first saw a poster in Belfast with the blunt declaration: “If the Church has nothing to say about reconciliation, the Church has nothing to say.” In the spring of 2012, students in our new program in Istanbul—led by Jim Wright and Heather Keaney—participated in interfaith dialogues, while our current students in Jerusalem, guided by Bruce Fisk and Tom Fikes, are listening to multiple factions in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

About a year ago, I visited a study program in Israel, where we heard a Jewish religious scholar assess the ongoing debate about whether absentee ballots should be permissible in Israeli elections. On the one hand, he summarized the view that in a mobile, technologically linked world it should be possible to carry rights as a citizen of Israel while working abroad. On the other, he described the concern that expatriates should not be allowed to vote on policies that might intensify violence or risk for residents, especially in a region where hostilities constantly loom. The debate epitomizes the challenge of reconciling the global and the local—or the extent to which the flat world, for all its expediencies, masks some of the starker realities of the contoured spaces where we live and breathe.

Not long before going to Israel, I had read a contemporary theologian’s commentary on Genesis 25, which describes Isaac and Ishmael coming together to bury their father, Abraham, in the cave at Machpelah in a field at Ephron. In the scholar’s mind, that text serves as an emblem of the potential for modern ecumenical trust. Yet that inspiring vision seemed all the more elusive and urgent to me after visiting Abraham’s supposed burial sitewith students in contemporary Hebron. The old Herodian structure built over Abraham’s cenotaph and the subterranean cave is now divided into separate sections for Muslims and Jews, both framed by heavily armed guards and metal detectors. This has often been a setting for violence: grenades thrown in entrances, a gunman on rampage in the mosque. Being there on that ancient and often tragic space can be ominous, disconcerting. But being there can help all of us see that it will take more than polemics for the vocation of peace. Talking with students after our visit showed me just how much their own sense of their future work and study had taken new cues from what they had been witnessing over their months in the Middle East.

Growing up in Garden Grove, Calif., I made my first journeys abroad just as the demographics of my town began to change. My first academic experience overseas took me to Rome, London and Paris; the end of the Vietnam War witnessed the arrival of immigrants to my neighborhood from Saigon, Phnom Penh and Seoul. Most of the store signs along Garden Grove Blvd., near my childhood home, are printed in Korean, and more than one-quarter of the residents are Vietnamese Americans, the second-highest concentration in any American city.

In some ways, this mirrors the different streams of college students to and from the United States. Europe has long been the favored destination for American students, though the population of international students in the United States is predominantly Asian. Nearly 55 percent of the Americans in study-abroad programs still venture to Europe, with England, Italy, Spain, France and Germany commanding almost all the attention. But today more collegians come to America from Vietnam than from any European country and only Turkey—with a foot in two continents—represents Europe among the top-ten sources of international students in the United States. No South American, African or Oceanic nation appears on that list.

The most active Asian nations, though, have changed with political and economic currents. In 1979—on the eve of the American hostage crisis in Teheran—Iran provided the most. About 55,000 Iranians came to American colleges or universities that year, largely due to the Shah of Iran’s aggressive efforts at Westernization. Saudi Arabia recently emerged as the major sponsor in the Middle East, drawing upon its massive oil profits to sponsor study abroad in the aftermath of September 11. But no nation today comes close to China. China’s growing economy makes it more likely that students will be eager to study overseas and then to return home. The single-child policy has allowed parents to devote resources to a sole college degree, and the nation’s deep investment in primary and secondary education is paying off with more college-bound youth. Between 2009 and 2011, the flow of Chinese students to American colleges and universities doubled, reaching nearly 200,000 and exceeding the next two nations—India and Korea—combined.

Asia represents a new horizon for international study at Westmont. We’ve enjoyed longstanding connections to a program in Thailand, and I expect we will cultivate greater opportunities in the Far East and Southeast Asia. Yet when I consider the contrast between the flow of students in and out of the United States, I realize that we can too often perceive international education as primarily venturing overseas, rather than coming to know the global citizens in our neighborhoods.

For a film series I hosted a few years ago, I chose Zhang Yimou’s “To Live,” one of the Chinese films best known in the West, largely because of its melancholy depiction of life during Mao’s Cultural Revolution. One Chinese student—an economics major—joined me for post-film commentary. With some brief preparation online, I was ready to trace the film’s narrative ironies and political undertones, but all that seemed only cursory and second-hand when I heard her reflections on the film’s visual textures—the color of the cloth, the silent gestures and glances, the many nuances lost in my viewing. This was a film that her family loved because it evoked something about their sense of disjunction and continuity with the past. Only after hearing her comments on the cinematography and dialogue could I begin to imagine how this story about a couple’s love for their daughter during an era of limited possibilities would resonate now for a daughter whose parents had made it possible for her to study on the other side of the world.

A few years later I prepared for a trip to India by reading some of the recent Indian novels to win the prestigious Booker Prize in London, only to be cautioned by scholars in southern India about only choosing the Asian books with sufficient irony to secure Western prizes. They shared with me poems and stories about the dark soil in the Nilgiri Hills and the wind over Cape Camoran; I thought of the times I have shared an essay by Thoreau or a poem by Frost chiefly because they were about places that I loved. Art, literature and film can open superb windows on other cultures, some of the best ways of internationalizing the curriculum and bringing the world closer. But we still need to temper our own interpretive confidence by listening to those who know the idioms of their native places.

The importance of truly hearing those idioms underscores some apprehensions about another trend in international study: the rapid surge in short-term study-abroad programs. Such programs—generally offered during the summers—have seen a five-fold increase since 1990. Once the staple of international exchanges, one-semester programs now represent only 34 percent of the total. This means more students are encountering other cultures, kindling new appetites for scholarship and service. But several studies—such as the Georgetown Consortium Project—suggest that short-term programs can often increase ethnocentricity. Having visited many nations on short-term assignments, I have made my own hasty generalizations that needed correction by more seasoned observers and citizens.

Quite interestingly, though, students who experience substantial immersion in another culture—even many who live in homestays or take all courses at an international university—can often show disappointing results on post-trip tests of intercultural development and understanding. The Georgetown study reveals that students who spent 25-50 percent of their time with nationals experienced the greatest maturation and growth in cross-cultural empathy. Although such studies are preliminary, they hint that too little interaction led to students being under-challenged and too much interaction led them to feel overwhelmed. Like other studies, the George town project demonstrates the necessity of seeing study-abroad as part of the tapestry of a student’s full collegiate experience and not simply as isolated, self-contained interludes.

According to the research, two of the most vital pieces of that tapestry are the presence of supportive interpreters from their own culture on the trip and an intentional program to help students with re-entry upon return. Nearly half of Westmont’s full-time faculty members have guided international programs—English professor Paul Delaney leads the pack with 18—making them considerable mentors. Since its inception, the Westmont in Mexico program has required a re-entry seminar, a practice the new program in Istanbul has also adopted. While we may still call our programs “off-campus” ones, the faculty’s commitment to travel and learn with students invigorates the on-campus conversations about world issues and can provide some support when they return.

Three years ago, Arlyne and I visited our son Daniel—at that time, a Westmont junior—during his spring term in Seville, Spain. Westmont has sent many students to Seville, and Daniel heard good words about the program from his peers. While abroad, he lived in the Triana neighborhood on the western bank of the Guadalquivir River, a district known for its pottery and its heritage as a birthplace of flamenco dance.

In our few days there we tried to soak up as much as we could of his new environs, but I had my own small pilgrimage in mind. In the 15th century Triana was at the heart of the Spanish Inquisition. At the river’s edge, just below the Triana Bridge and a small Moorish revival chapel, Daniel and I visited the ruins of the old dungeon of the Castillo San Jorge. Fiction drew me there, not history. The Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky located an imaginary encounter between Christ with the Grand Inquisitor—the most famous chapter in his novel “The Brothers Karamazov”—in the dungeon of Seville. That novel, more than any other, provoked some of the richest spiritual conversations during my own senior year as a literature major. I wanted to recover that moment of yearning and discovery with my son; it was one way of talking about my own journey of faith.

What did we recover there? Most of the walls in the dungeon’s interior had crumbled, and the well-lit pathways and meticulous excavation gave the underground chambers a colorless, orderly sterility, a far cry from the damp, claustrophobic compartments where the incarcerated often died. It was a long way from Dostoyevsky’s angst or my own youthful soul searching. But all journeys are blends of expectation and discovery. At that moment, we were a father and son from different generations, each with new books we wanted to share, new questions, new perceptions, standing together on a new ground that made fresh conversations possible. My pilgrimage had blended into his sojourn.

Exiting the dungeon, we passed immediately through a new indoor market, and our conversation turned from the Inquisition to the numerous posters of Semana Santa, the great Holy Week festival that culminated in a procession across the bridge. Daniel had his own accounts of the religious ceremonies and conflicts in Spain. We talked about where his classes were taking him: into issues of inquisition, immigration, unemployment and regional separatism. Studying Spanish made it possible for him to converse with elders who knew the fearful silences and suppressions of the Franco years. The semester left its imprint: he’s in graduate school now, writing about how journalists shaped events at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

Many of these sources are available online. With Twitter, journalists and activists can shape public demonstrations and events. The world is flatter. No doubt, MOOCs and other online variants will reach many underprivileged, and smart phones will play their own roles in empowerment and justice. But there are still some archives in dusty libraries, and many memories, human needs and untold stories beyond cyberspace. There are still pilgrimages and journeys that are more than the exchange of knowledge but the shaping of lives. When I hear stories from students about candlelight walks in Canterbury Cathedral, meals with Mexican families, or sunrise services in South Africa, I recall something that has always held a central place in the community of Christ: the value of being present in body and in spirit.