Westmont Magazine Reflections of a Cult Watcher

By Ronald M. Enroth, Professor of Sociology, Westmont College

Theologian Ronald Sider published an article in the Christian Scholar’s Review in 2007, “Needed: A Few More Scholars/ Popularizers/Activists: Personal Reflections on my Journey,” that described the various roles he’s played in his career. He spent several years of specialized study completing a doctorate at Yale but only taught one course in his area of specialization, the 16th century Reformation in Europe. Most of us know his book “Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger,” but not his scholarly work on the 16th century reformer Andreas Bodenstein van Karlstadt.

I spent five years of graduate study and completed a doctorate in medical sociology, but I have only taught a related course once or twice. I was one of the first persons to earn a degree in medical sociology at a medical school: the Department of Behavioral Science at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine. I planned a research-oriented future only to find myself starting my professional career at a Christian liberal arts college in California. I told my doctoral committee I would stay at Westmont for only a year or two. That was 47 years ago, and the college hasn’t offered a course in medical sociology in decades.

Sider describes himself as a popularizer, and that label fits me too, although I lack his stature. His article helped me sort out several things I’ve encountered in my own professional pilgrimage.

I’ve wondered if there is a role for a popularizer in Christian sociology, and I’ve speculated about how different my life might be if I had pursued medical sociology. Some of my colleagues may look askance at combining popularizing with scholarly work and activism. But I’m convinced that such a role belongs in the academy, especially evangelical Christian higher education. I agree with Sider, who writes, “Evangelicalism, especially, with its strong anti-intellectual strain, has often—whether one thinks of eschatology, science, family life, or politics—been badly served by popularizers and activists with simplistic ideas and superficial solutions. Nor will that change unless more people with good scholarly training become effective popularizers and successful activists.”

A “popularizer” is a person with traditional, graduate-level academic training whose work appears in non-traditional forms of publication (trade books rather than university presses) and who accepts invitations to appear in various media outlets. I’m the only Westmont professor to be on the Oprah Winfrey show, and National Public Radio has interviewed me several times. I believe that popularizing can be an aspect of public sociology.

A popularizer is more likely to speak to youth pastors at the YMCA of the Rockies in Estes Park, Colo., about “The Appeal of Cultic Religion in Today’s World” than to present a paper on “Individual Differences in Religion and Spirituality: An Issue of Personality Traits and/or Values,” at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion in Chicago.

While in graduate school, I co-authored two scholarly articles published in academic, medical journals. I was on my way to a career in mainline research, and it was exciting. For a number of reasons, I decided to interrupt that path by accepting the position at Westmont. My first opportunity to become a popularizer and contributor to the chronicles of contemporary events occurred early in my career. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Jesus Movement hit the religious scene in America, especially in California. Hippies and drug addicts started becoming Christians. Jesus Freaks and street Christians received considerable attention in both the secular and Christian press.

Three of us, Ed Ericson (then an English professor at Westmont), Breck Peters (a senior sociology major and brilliant writer) and I, sketched out a three-page prospectus for a book about the Jesus Movement. None of us had published a book before, so in spring 1971 we decided to submit our brief outline to an esteemed Christian publisher, William B. Eerdmans. The folks at Eerdmans were so impressed they offered us a contract without requesting additional examples of our writing or other proof of our capability. Because of the currency of the topic, they wanted a completed manuscript by the fall.

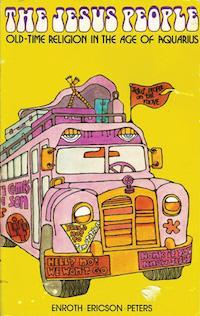

When “The Jesus People” came out in 1972, it was unlike anything Eerdmans had ever published. The cover featured an almost psychedelic, colorful, beat-up, hippie school bus with bumper stickers such as “Hell? No! We Won’t Go” and “Honk if You Know Jesus.” Photographs included beach baptisms, musician Larry Norman, Chuck Smith of Calvary Chapel, the early days of the Children of God, and, of course, Jesus watches. We had fun making up chapter titles such as: “The Simple Gospel: If You’re Saved and You Know it, Clap Your Hands”; “Power to the People: Getting it On with the Holy Spirit”; “Christian Communes: The Abundant Life Family-Style.” Talk about popularizing! But the book became something of a best seller in both hardback and paperback. It represents an example of semi-popular, semi-scholarly writing aimed at a broad audience.

Of the three of us, I’m the only one who remained involved with cults and new religious movements. In the book we differentiated between cult-like groups such as the Children of God (later known as The Family) and what we predicted would evolve into more traditional Christian churches, such as Calvary Chapel. The book inspired a flow of inquiries and requests for information or advice that continues to this day. I have found a ministry working with people emerging from cults or abusive churches and with parents concerned about their children’s involvement with such groups. Their stories and needs have inspired my continued research and writing in this area.

I published “Youth, Brainwashing and the Extremist Cults” in 1978, just a few months before the tragedy of the People’s Temple in Jonestown—an event that raised awareness of cults. The book changed my life as an author and sociologist. In part because of Jonestown, it became a bestseller with at least 10 printings. I was unprepared for the media onslaught that followed as reporters hounded me for interviews. My book was one of the few works by an academic about allegations of brainwashing on the part of extremist religious groups.

Interacting with the media can be time-consuming and frustrating. When the story of the Heaven’s Gate suicides broke, I was on the phone in my office with media people from 8 a.m. until at least 6 p.m. I stopped counting requests for interviews at 70. Three years ago, I gave a two-hour interview to a filmmaker doing a documentary on two new religious movements; only two minutes appeared in the final piece, which aired on the A&E Network.

Professor Sider expresses frustration that popularization requires simplification: “…good popularizing demands that one set aside many complexities in order to offer a clear, coherent statement of the central issues. That easily frustrates the popularizer—who is also a scholar—not to mention the scholarly critics who are not popularizers!” He correctly notes that the popularizer “runs the danger of losing touch with his or her field of scholarly expertise.”

Not only is my popular writing on new religious movements and spiritually abusive churches far removed from my early work, but it took considerable time to read the relevant literature in the sociology of religion, an area in which I was not formally trained. I served as the editor of a special issue devoted to new religious movements for Social Compass, an international scholarly journal, but beyond that effort and participating in a few scholarly conferences focused on this topic, I have devoted whatever time remains after my teaching obligations to writing popular books published by Christian publishing houses such as InterVarsity Press and Zondervan.

Like Ron Sider, I discovered the general public has little interest in highly technical, detailed writing that doesn’t apply directly to issues of great human need. But combining the roles of scholar, popularizer and activist isn’t easy. As Sider said, “I would discourage anyone from trying to do it unless you felt called, and both experience and friends confirm that you have the necessary gifts and thereby confirm that call. Not many people should do it! I do not mean for a moment to urge most scholars to abandon a life of extended, focused scholarly research in their specific area of professional expertise. What I have tried is not for everyone.”

There are consequences to writing op-ed pieces, publishing popular books on controversial topics, appearing on radio or TV programs or being quoted in newspaper articles. Over the years I’ve received serious legal and personal threats. One letter stands out in my memory. The salutation began: “Dear Ron Enroth (Garbage Pig) 2 Timothy 2:3.” The passage: “Take your share of hardship like a good soldier of Christ Jesus.” The handwritten, rambling letter— partly in Spanish—concerned comments I made on a radio talk show regarding the writer’s pastor. Twice he wrote, “You will be destroyed. You are the scum of the earth, baby.” He continued, “If there is any wisdom in the college in which you teach, then they’ll dump your butt now or be destroyed with you. The Holy Spirit told this to me. No swine has a soul. I say no pig goes to Heaven…Most important, repent and go to work for Christ. Baby you gonna die.”

One summer day, I was checking my voice mail before leaving town for a vacation with my wife. A male voice spoke partly in rhyme, and parts of it were unintelligible. It began with, “Tick tock, tick tock, tick tock. Last night I started the clock. And now before the day is finished, the number of your comrades will diminish. Tick tock, tick tock, tick tock. The bomb is ticking somewhere at your college and you can’t stop it for all of your knowledge. If you think killing for God’s work is sinning, Dr. Enroth this is just the beginning. Tick tock, tick tock, tick tock.”

The police arrived at my office 10 minutes after I contacted them. They traced the call and made an arrest. In the meantime, President Winter closed the campus for the rest of the afternoon. I have taken security measures as a result of such threats—including removing my name from our home mailbox. Many of these attacks came because I interviewed ex-members, whom such groups consider traitors or worse.

Members of the Westmont board of trustees and administration as well as some of my neighbors received unsigned letters about me. One, from the non-existent organization Americans United to Protect Constitutional Rights, mixed believable material with misinformation and slanderous content intended to raise questions about my activities and motives: “His vicious anti-religionist stance is particularly alarming in that Westmont College is a nondenominational institution. One can only wonder why the administration of a Christian college would tolerate Enroth’s Inquisitionlike attacks of any religious groups that show differing views to his own…we are shocked that a man of his reputation and record is still allowed to teach at Westmont College.”

Surprisingly, I have encountered equally strong opinions from at least one well-known sociologist of religion, who acted as an expert witness in a legal case in 1995 to which I had no connection. In his legal deposition, he labeled an organization composed largely of concerned parents a “sophisticated hate group” and named me as one of the few sociologists who would associate with such a group, which he compared to the Ku Klux Klan and anti-Catholic, anti-immigration and anti-Semitic organizations. He never responded to my request for documentation of his outrageous comments.

In Christian higher education we stress the integration of faith and learning in all our disciplines. Whether we publish in nonscholarly venues or in more traditional academic outlets, we need to demonstrate that education is a Christian vocation, a “wholehearted response to God,” as Arthur Holmes said so eloquently. In his book “The Idea of a Christian College,” Holmes writes: “The Christian college is distinctive in that the Christian faith can touch the entire range of life and learning to which a liberal education exposes students.”

Secular sociologists tend to extol a value-free approach to their discipline. It’s difficult if not impossible for Christian scholars to research, write and teach about cults and new religious movements without examining the truth claims of such groups and discerning their differences from historic, biblical Christianity. That kind of thinking alarms secular sociologists. However, I’m convinced we must resist the temptation to reduce the challenge of the cults and new religious movements to sociology or psychology alone. Years ago I made a decision to follow my heart, to engage in a real ministry: writing that is informed by scholarship and directed at helping people who’ve experienced great human need. In some sense, I’ve tried to be the voice of the voiceless. The dedication page of my book “Recovering from Churches that Abuse” reads: “To all those hurting Christians who thought nobody cared or understood. You are not alone.”

Christians who’ve been abused find few people believe them or take their stories seriously. A former member said, “One of the most painful feelings I’ve had in the recovery process is the damage to my self-esteem caused by having what I say and think ignored. It feels like being erased as unimportant, like I don’t matter or don’t count. But I do. I exist and I’m real. These things happened to me, a person with a name, a face, feelings, and a life. My hope is that you will lend me and other ex-members your voice.” What a calling! What an opportunity.

Fortunately, I have received many more positive letters, phone calls and e-mails than negative ones. These statements make my work worthwhile. For example, a woman who read“Recovering from Churches that Abuse” said, “I felt compelled to write you this letter to tell you how much I have been helped by your research into this matter. I have been a born-again Christian for a very long time, but have had difficulty fitting in among other Christians. I have found them to be pretentious, self-righteous, critical, judgmental—everything but loving. After reading your book, I felt like a weight had been lifted from my shoulders. I felt less alone in the world. There were people out there who had been injured and feeling as hopeless as myself.”

Like Ron Sider, “I hope that a few in each generation of Christian scholars will pray for the gifts, develop the skills, and pay the price of becoming far better popularizers and more effective activists than I have managed to be.”

Ron Enroth retires this year after 47 years at Westmont. See the related story here.